The Beginning of the Sevashrama Movement

June 13, 1900. The day had not yet dawned. Jaminiranjan was winding his way through one of the narrow dingy lanes of Varanasi leading to the bathing ghat. A feeble groan caught his ear. Many had already passed that way, but no one had stopped to investigate. But Jaminiranjan did and found an old lady, ill and starved, lying on the roadside. As he approached her, she said feebly: ‘I have not taken anything for four days, my son. Give me some food.’ Jaminiranjan lifted the lady and laid her carefully on the verandah of the nearby house, rushed to the bathing ghat, and begged four annas from the first gentleman he met. He purchased some cooked food and fed the old lady and thus saved her life. Thus was sown the seed of dedicated service to God in the form of the poor and the suffering, which was to grow into a mighty banyan tree of a large institution that would render service to thousands of needy.

This old lady was one of the many religious persons who come to spend their last days in the holy city of Kashi — the mukti kshetra — and who are reduced to a state of dire poverty and helplessness due to the ruthlessness of man and the irony of fate.

The First Sevashrama at Varanasi

After rendering this emergency help to her, Jaminiranjan went to his friends Haridas, Charuchandra (later Swami Shubhananda), Kedarnath (later Swami Achalananda), and others, and gave them an account of what had happened. A band of young men with Charuchandra as the leader had already formed a study circle with the aim of realizing God in the light of the teachings of Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda. They collected donations and managed to admit the lady to the hospital. The new group now decided upon future action: service to the poor, the needy, the destitute, and the sick. They organized themselves into an association and named it ‘Home of Relief’. They searched for the needy on the roadside, in lanes and by-lanes, and arranged for their relief by sending some to the hospital, and giving food and clothing to others. A patient of typhoid fever was the first patient to be accommodated in Kedarnath’s house and nursed by them. Soon the need for more spacious accommodation for patients was felt and a small house was rented for five rupees a month. A small out-patient homoeopathic dispensary was also started. One room was for hospital patients, and the dispensary was also the office and the bedroom of two full-time workers — Charuchandra and Jaminiranjan.

Soon the enthusiasm, dedication, and indefatigable labour of the young men attracted the attention and sympathy of prominent citizens, on whose advice the first general meeting of the association was held on 5 September 1900, at which it was renamed ‘The Poor Men’s Relief Association’. Within six months the hospital and out-patient relief work increased so much that a more spacious house at Dashaswamedha Road had to be rented, which was later shifted to a bigger house in Ramapura in 1901. Within eighteen months 330 men and 334 women received treatment.

In February 1902, when Swami Vivekananda visited Varanasi, he was highly pleased by the work done by the association. However, he advised them to change the name to ‘Home of Service’, for, as he said: ‘Who are you to render relief? You can only serve. The pride of rendering relief leads to ruin… How arrogant it is on the part of a man to think another lower and humbler than himself? Service and not mercy should be your guiding principle — service to man, the image of God.’ He turned to Charuchandra and said: ‘Regard every pice collected for the poor as your life-blood. Such noble work can be carried on properly and permanently only by those who have renounced everything.’ Swamiji wrote an appeal to the public on behalf of the Home of Service, which accompanied the first report of the Home in 1902. Swamiji also instructed Swami Brahmananda to keep a watch on the organization. With the latter’s approval and by a resolution of the managing committee of the Home of Service, the association was affiliated to the Ramakrishna Mission and came to be known by its present name, ‘Ramakrishna Mission Home of Service’, on 23 September 1903.

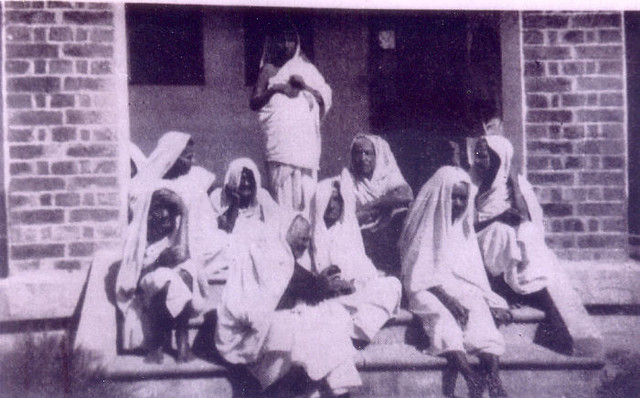

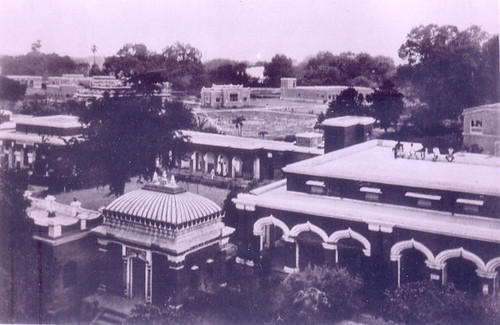

Things moved fast thereafter. Unexpected donations from two donors, and an equally unexpected offer of a plot of land for a paltry Rs. 6000/- enabled the Home to have a place of its own. Here Swami Brahmananda laid the foundation stone of the future building on 16 April 1908. Swami Vijnanananda was the chief architect, and the new building was inaugurated by Swami Brahmananda on 16 May 1910. The Holy Mother visited the Home of Service on 8 November 1912 and, having been taken round, was extremely delighted and exclaimed, ‘Thakur himself lives here and Goddess Lakshmi has chosen this place as her abode.’ The ten rupee currency note donated by her is still preserved in the Home as a sacred treasure and blessing.

Documentary on Ramakrishna Mission Home of service, Varanasi, India

The Kankhal Centre

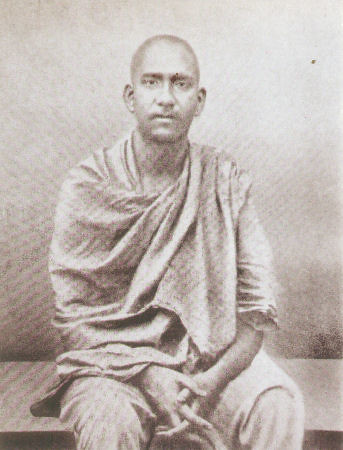

Let us now review the events occurring almost simultaneously at Kankhal. Swami Vivekananda, who, from personal experience, knew the helpless condition of monks living at Hardwar and nearby places, told Swami Kalyanananda: ‘My boy, can you do something for the ailing monks at Hardwar and Rishikesh? There is none to look after them when they fall ill. Go and serve them.’ In June 1901 Kalyanananda began his work at Kankhal, a village near Hardwar. Two rooms were hired at Rs. 3/- per month, which served as his dispensary, hospital, bedroom, office, and everything. His stock of medicine was contained in a box. Living on alms, the Swami distributed medicines not only to those who came to him, but also to those who could not or would not stir out of their huts to visit them. He was soon joined by Swami Nischayananda, another disciple of Swami Vivekananda. Ignoring physical hardship, the two monks opened a dispensary at Rishikesh, which was like a branch centre fifteen miles from Kankhal, to serve the needy walking all the way to and fro every day.

Apart from treating monks in their huts, they would also perform the last rites of those monks who had died in their huts and had no one to perform these rites. They did not restrict their medical service to the monks only, but extended it to the untouchables and the so-called outcastes. As a result, on the one hand they were castigated as untouchables — bhangis — by the majority of the orthodox monks of the towns of Rishikesh and Hardwar, and on the other, they were highly respected by others, of whom Mandaleswar Swami Dhanraj Giri was the foremost. Once it happened that at one sádhu-bhandara — a feast for monks — hosted at one of the Maths, the ‘out-casted monks’, Kalyanananda and Nischayananda, were not invited. When Mandaleswar Dhanraj Giri, the chief guest, learnt this, he rebuked the orthodox monks and said that those two monks were truly practising the Vedantic tenets of ‘all is Brahman’, and unless they were invited and honoured he would not accept hospitality. This opened the eyes of the orthodox monks, and their antagonism towards the two monks soon vanished.

Their dedicated service soon attracted the attention of people and help started flowing in from various quarters. A plot of land was purchased in 1903 and the first building of two blocks, designed by Swami Vijnanananda, was constructed on it. The Sevashrama was shifted to its new premises in 1905. In 1911 another ward of twenty beds was added and a tuberculosis block was inaugurated in 1913. By the end of 1922 the number of beds had risen to 66.

It is needless to mention that the work of service was wholly free and was supported by charity and donations, which ranged from a meagre four annas to a thousand rupees or more. The monks sustained themselves by mádhukari-bhikshá — begging food from door to door. Two others, Swami Japananda and Brahmachári Suren, also went for bhikshá and thus reduced the burden on the Sevashrama. However, there were practical difficulties involved in simultaneously begging and managing the affairs of the hospital. Realizing this, Swami Saradananda, the General Secretary of the Mission, intervened, and on his instruction in 1921, the tradition of bhikshá was given up in the interest of greater efficiency. But both Kalyanananda and Nischayananda regretted being deprived of the splendid freedom of begging.

The Emergence of other Centres

The next Sevashrama to come up was at Vrindavan, where there was no facility for treatment of the multitude of pilgrims. In January 1907, taking their cue from the activities at Varanasi Sevashrama, some local people organized themselves into a committee to start a Sevashrama, of whom Jajneswar Chandra and his son were the central figures. They were joined by Brahmachári Harendra of Belur Math. The Sevashrama was initially located in the outer area of Kalababu’s Kunja, the ancestral property of Balaram Bose, where the patients were accommodated. The management passed on to the Mission on 12 January 1908, and in 1912 the number of hospital beds had gone from four to fifteen. A plot of land measuring 8.32 acres was secured in 1915 on which a temporary structure was constructed so as to shift the Sevashrama from Kalababu’s kunja. Gradually a male and a female wards were constructed.

The next Sevashrama to come up was at Allahabad in 1908, followed by many others, viz. Lucknow (1914), Contai (1913), Bankura (1917), Sonargaon in Dhaka (1915), Garbeta, Midnapur, etc. These Sevashramas were a very important feature of the Ramakrishna Mission’s medical services, since whatever aspect the numerous subsequent activities assumed — whether dispensaries, hospitals or polyclinics — they were, as it were, the great branching out of the Sevashrama Movement. The organization of a Sevashrama is simple enough: the monks dispense medicines or attend to and nurse the patients personally. For the first time, perhaps, in the history of Indian monasticism, sadhus confronted God in pain and suffering and in need of the worship of care. The monks thus clearly demonstrated that the invalid, the forlorn, the diseased, and the poor were their God. Persons lying uncared for by the roadside were special objects of their adoration. Inspired by the examples of Swamis Shubhananda and Achalananda, and Kalyanananda and Nischayananda, many young workers, monastic and non-monastic, professional doctors and untrained workers, came forward to render their service.

It must be remembered, however, that the work of the Sevashramas was not always smooth sailing. The fact is that during the early decades there was always financial difficulty. The period of the first World War between 1914 to 1919 was especially trying. Then there were people who vacillated in helping. One person, long after making a donation for building a ward in memory of his father, started doubting the integrity and permanency of the work and imposed such conditions that the Sevashrama had to borrow the amount from another source and return it to him. However, the monks did not always rely on human help to get over financial difficulties. They had firm faith that they were doing the Lord’s work, and during financial stringency, they would do collective or personal introspection to find out whether they were deviating from the ideal. It was observed that as soon as any imperfection or error was spotted and corrected, help flowed in and the difficulty disappeared.

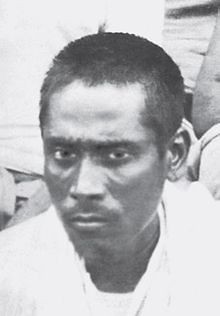

The attitude of the workers of the Sevashramas is perhaps best expressed in the words of Swami Nischayananda to ‘M’. Seeing Swami Nischayananda engaged day and night in work, ‘M’ remarked: ‘Look here Nischay, Thakur used to say, “The ideal of the sadhu’s life is God realization, and not mere work.”’ When ‘M’ repeated this twice or thrice, Nischayananda could not control himself, and bursting into tears he said with folded hands, ‘I am Swamiji’s bond slave; I know no other spiritual practice than work, to which I have been commissioned by him. I have vowed to hold on to this path.’ ‘M’ was not only silenced but understood and apologized. Another monk was engaged in the work of growing vegetables in the fields of Varanasi Sevashrama. When asked why he was thus labouring in the scorching sun when as a monk he should have been reading the Gita or meditating, he replied unambiguously: ‘Why, I am growing vegetables which will be eaten by the sick-Narayanas.’ Another monk also had spent his whole life dressing the wounds of the ‘sick-Narayanas’ to the extent that his knees became stiff due to constant standing. For these monks, work was worship, and the ideal of ‘for one’s own liberation and for the good of the world’ was ever bright before their eyes.

These earliest Sevashramas had the great privilege of having the blessings and guidance of Swami Brahmananda, the first President of the Mission, and other great direct disciples of Sri Ramakrishna, who visited these centres whenever possible. Swami Turiyananda lived at Kankhal for some time and passed his last days at Varanasi. The very presence of these spiritual giants would raise the minds of the workers to a higher spiritual plane. They, and the earlier pioneers, instructed the workers so that they could work in the spirit of consecration and check the work from becoming degraded into a mere secular activity. Swami Achalananda, for example, would never use the word ‘patient’. Instead he would say ‘Narayana’, and expected everyone else to do the same.

Documentary on Vrindavan Sevasrharama

Later Developments

The next phase in the development of medical services of the Ramakrishna Mission was marked by the starting of regular medical institutions — hospitals or out-patient dispensaries for the relief of medical problems in the community. The starting of Shishumangal for maternity and child care in Calcutta, the charitable tuberculosis clinic at New Delhi, and the tuberculosis sanatorium at Ranchi are three such institutions. This phase also included the much needed upgrading and modernizing of the Sevashramas.

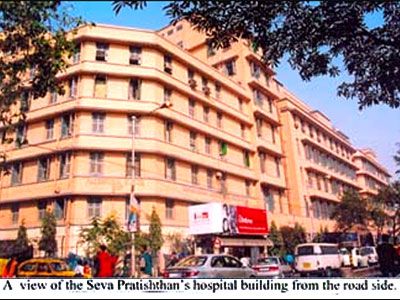

While in the USA, Swami Dayananda was greatly impressed by the medical advances there. After returning to India in 1931 he started a centre called ‘Shishumangal’ (Children’s Welfare) in Calcutta with only seven beds ‘with the object of safeguarding maternal and infantile health’. This maternity, pre-natal and post-natal care hospital, due to its remarkable efficiency, soon became well known, and in 1939 it had its own building with fifty beds and auxiliaries. It was expanded into a General Hospital in 1956, and in 1957, it was renamed ‘Seva Pratishthan’. It is now a giant institution of 550 beds with four wings: (a) General hospital, (b) School of Nursing, (c) Post-Graduate Medical College and Research Centre, and (d) Community Health Service. Recently, in October 2005, a College of Nursing was inaugurated there with BSc (Hons) course.

Documentary on Ramakrishna Mission Seva Pratishthan

Because of the high incidence of tuberculosis in India, it was decided to start a tuberculosis sanatorium. Accordingly, in 1939, 240 acres of land was acquired at Dungri in Bihar (presently in Jharkhand), ten miles from Ranchi, and the sanatorium was opened in 1951 with 32 beds. It now has 280 beds with several ancillary departments. At Delhi, too, there is a TB clinic started in 1948, which has a well-equipped diagnostic laboratory. It also has a home treatment scheme under which health workers and doctors are deputed to educate and treat those who do not attend the clinic. These two TB institutions have been acclaimed as among the best in the country.

Apart from the centres engaged solely in medical service, various Math and Mission centres started charitable out-patient dispensaries, which, in the course of time, developed into well-equipped dispensaries providing allopathic and/or homoeopathic treatment. Some have their unique features, e.g. ayurvedic treatment, physiotherapy, acupuncture, etc. The 275 bed hospital at Thiruvananthapuram has a psychiatry section. One of the recent developments has been the introduction of Mobile Medical Units by a number of medical centres, enabling them to extend medical services to those remote corners of rural and tribal areas which had remained mostly inaccessible.

The Kankhal Sevashrama has also been upgraded. An overhead water tank was constructed in 1953, and the doctors’ quarters and x-ray block in 1956. It is now a hospital of 122 beds. The Vrindavan Sevashrama started an eye hospital in 1943, which has since then earned a very good reputation. These hospitals were greatly benefitted by equipment and other grants from State and Central governments during this phase of modernization. The government grants, however, are neither always available nor adequate, and the institutions have to depend upon public donations. Yet most of the institutions are able to render free medical service to a substantial proportion of their patients.

Realizing the need for modernization and upgrading, the Varanasi Sevashrama opened a block with an operation theatre and a dressing room for women in 1948; two x-ray units were installed in 1951; and a building to house diathermy and infra-red equipment was constructed in 1953. In 1955, the out-patient department was extended, and in 1956, a surgical ward with 18 beds was constructed in the women’s department. It is now a full-fledged hospital of 230 beds, with a busy operation theatre and surgical department, and almost all specialities and some super-specialities. A number of visiting consultants and specialists render honorary service, and some resident doctors are appointed.

It is not possible to go into the details of the growth of each institution. We have therefore tried to describe in some detail only the oldest and the most representative.

One of the special features of the Mission institutions is their achievement of the best possible results and a high standard of service — both technical and humanitarian — with the least possible expenditure. This is partly due to the honorary services offered by local medical practitioners. The personal care taken by the monks adds to this economy and efficiency. In many hospitals, monks act not only as administrators but also as nurses, compounders, dressers, and doctors. And because of the presence of these monks, who consider their duty a service to God, and attend personally to the details and bestow sympathy to all irrespective of the caste, creed, and social status of the patient, the patients feel quite at home in these institutions, a fact which explains their continuous public acceptance.

Conclusion

Today the Ramakrishna Mission’s medical services range from the humble homoeopathic dispensary to the super-speciality hospital. Yet it does not boast of its numerous medical centres, the large number of patients served, or the high technical sophistication achieved by some of its institutions. Its glory lies in the spirit with which patients are served. Serving one patient with the right attitude, truly considering him a God, is far superior to serving a multitude without it.

The medical scene has undergone a great change during the past few decades. The disease patterns have changed and new concepts of health care and medicine have evolved. These changes can be summarized in three words: commercialization, technicalization, and globalization. Medicine today is no more the humanitarian art and science that it used to be, but has become a lucrative business — something which was decried in no uncertain terms by Sri Ramakrishna more than a century ago. While technical advancements have wrought wonders in certain fields, it has made modern medicine extremely expensive, elite-oriented, and beyond the reach of the common man. Communicable diseases and problems of socio-preventive medicines related to poverty and sanitation have assumed gigantic proportions in a third-world country like India. The Mission has a glorious record of a century of medical service under difficult conditions. In this 21st century it will have to face these new challenges of providing cost-effective remedies and bringing the most modern medical, scientific and technological advances to the poorest in the remotest corners of India. At the same time it will have to maintain the high standard of dedicated service and motivate even the self-seeking medical practitioners to provide what little selfless service they can. The Mission has done this in the past and has the potential to do it for many centuries to come.