Prelude

Ramakrishna Temple, Belur Math, is a place of international pilgrimage significant due to the fact that Swami Vivekananda placed the relics of Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa here and envisioned a unique temple to house them.

Before his debut in the Parliament of Religions (1893) at Chicago, Swami Vivekananda had wandered about many historically important places of India looking for the signs of the greatness as well as for the reasons for the decline of her ancient culture.

Swami Vivekananda’s pilgrimage took him to many parts of Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Kerala, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu. He must have made profuse mental notes of his observations especially on the architectural monuments like the Taj Mahal, Fatehpur Sikri palaces, Diwan’I’Khas, palaces of Rajasthan, ancient temples of Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and other places.

During his tour in America and Europe, he must have come across buildings of architectural importance of Modern, Medieval, Gothic and Renaissance styles.

To pay tribute to the multifaceted, all-embracing divine personality of Sri Ramakrishna, he envisioned a great edifice combining various architectural features of monuments in various parts of the world. It was Swami Vivekananda’s desire that the new temple should embody the salient features of major temple architecture of different religious beliefs so that everyone who comes to the Ramakrishna Temple would feel at home and realise the underlying principle of the universal brotherhood and religion propounded by the Great Master.

| Ramakrishna Temple : Belur Math |

| 1. In the Garbha Mandira (Sanctum Sanctorum) of the Temple, Sri Ramakrishna's marble image is enthroned on a marble lotus platform with Braahmi Hansa engraved on it. His sacred Relics are preserved inside the platform. |

| 2. One Bhandaar (store of sacred articles) is annexed behind the Garbha Mandira bearing above the Shayan Kaksha (recline chamber) of the deity. The kitchen for preparing the bhoga (cooked food for offering), however, is at a separate place behind the Garbha Mandira. |

| 3. The canopy above the deity was made by a carpenter from Salkia (4 kms South of Belur Math) with a special teak wood brought from Burma (Myanmar). |

| 4. The Garbha Mandira rests on a concrete foundation slab of 27 square metres area and more than 1 metre thick. |

| 5. Thick stone slabs, bricks and concrete have been used in the walls of Garbha Mandira and only claddings have been done with chunar sand stone. |

| 6. Surki (brick dust) was prepared locally and sand was collected from Magra (near Panduah) of Hooghly District. |

| 7. Domes have been made of chunar stone, bricks and cement concrete. Galvanised iron strips have been used to resist tensile hoop stress. |

| 8. The floor of the Garbha Mandira and the Nat Mandira have been laid on with white and black marble stones respectively. |

| 9. The Nat Mandira and the Garbha Mandira are structurally separate. They are attached to each other by an expansion joint which is not easily visible to visitors. |

| 10. All the doors and windows of Garbha Mandira and the Nat Mandira are made up of choicest teak wood imported from Burma (Myanmar). The work was done by Chinese carpenters and the fittings were procured from a Bombay (Mumbai) based company at concessional rates. |

| 11. Lamp stands (made of copper) on the temple platform were cast by a local artisan. |

| 12. The estimated cost of the temple was six lakh rupees (1935), but on completion (1938), the actual cost came to around eight lakh rupees. |

| 13. Almost the whole expenditure of construction of the temple was borne by the generous donations from two disciples from USA. |

Three decades after the passing away of Swami Vivekananda, the idea was put into actuality by Swami Vijnanananda, another direct disciple of Sri Ramakrishna, with the help of M/s. Martin Burn and Company, the then famous architect builders of Calcutta.

In his discussion with Mr. Herald Brown, the architect at Martin Burn Co., Swami Vijnanananda stressed upon the following three features that Swami Vivekananda wanted to incorporate in this temple monument :

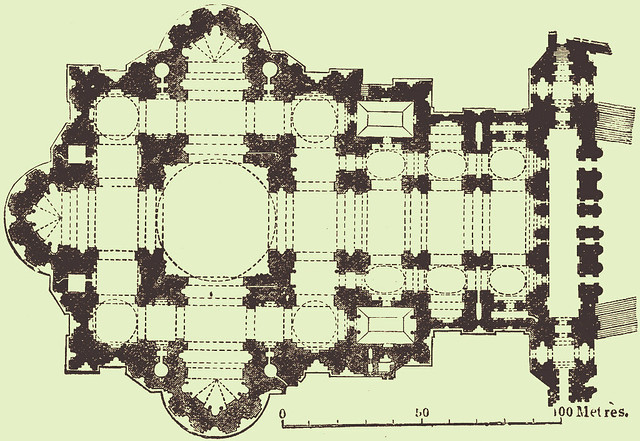

1. Natmandira (Congregational Hall) and Garbhamandira (Sanctum Sanctorum) should not be detached as in a Hindu temple but should be connected in a continuous space like that in a Christian Church.

2. Garbhamandira should have a domical roof as introduced in Mosques through Islamic Architecture.

3. Other rendering and detailing should conform with traditional Hindu temple architecture.

Two plans were submitted by the architect from which the one with more Indian tone was selected.

First foundation stone for Ramakrishna Temple was laid by Swami Shivananda on 13 March 1929, the birthday of Sri Ramakrishna. Swami Vijnanananda laid the foundation stone at the present site, 30 metres south of the first one on 16 July 1935. Construction was completed and consecrated on 14 January 1938.

| Major outer dimensions of the temple | Major outer dimensions of the temple | Major outer dimensions of the temple |

| Maximum | Platform | Superstructure |

| Length | 70.50 m (235 ft) | 61.00 m (202 ft) |

| Width | 42.00 m (140 ft) | 24.00 m (80 ft) |

| Height | 1.75 m (5.80 ft) | 31.20 m (104 ft) |

The Setting

As a visitor enters the Belur Math gate on the asphalted road to the temple, a variety of old trees camouflage the temple from his sight till about a hundred metres away, from where he gets a partial glimpse of it.

The site chosen for the temple by Swami Vivekananda is right on the holy river Ganges with a clear view of two important places related to Sri Ramakrishna—Dakshineswar and Cossipore, which add to its sanctity. In a spatial tribute to the Ganges, the temple has been located parallel to its flow, sufficiently away to avoid its water from entering during high tides.

The vast green spaces on both sides of the temple and in the front with a backdrop of long simple Math office building, the Math Library and residential quarters for monks complete its setting.

Not far from it are the old shrine, the remodelled Math cottage housing the room where Swami Vivekananda spent his last days and where many of the monastic disciples of Sri Ramakrishna stayed, and temples dedicated to Swami Brahmananda, the Holy Mother Sri Sarada Devi and Swami Vivekananda.

The simple but elegant pathway leading from the entrance gate bordered with a number of huge trees and the setting against the holy Ganges with the other bank silhouetted against the morning sun presents a contrast to formal settings of many ancient monuments of India like the Taj Mahal or the Victoria Memorial of Calcutta.

The Temple

The temple of Sri Ramakrishna is built in sandstone with parts of it in concrete. The light buff sandstone has been traditionally used since the times of Ashoka the The Great in northern India, especially in the Khajuraho temples and Rajasthan palaces as it is durable, soft enough to suit intricate carvings and is readily available. The Mughals used marble for their monumental buildings which however finds its place only in the elegantly inlaid black and white floors of this temple. The overall impact of the temple in perspective raised on a modest platform of about 1.75 meters is homely, decent and at the same time elegant.

Main Entrance

What a visitor is struck by when standing in front of the temple is its facade which reminds one of a South Indian Gopuram gate, difference being that the Gopuram entrance gates usually used to be detached from the main temple while the huge gateway here is attached to the temple and is composed of grand arches, chattris (canopies) and domes with a height and width which dwarfs the Nat Mandira behind.

The entrance has various elements which remind one of ancient Indian architecture in its various phases. The pavilions at the top suggest the contours of the roof pattern of palaces of Jodhpur and Udaipur though the curvature of chajjaas are more common in Bengal Temples.

The three scalloped arches of the central pavilion at top are beautifully balanced with the large main arch below which in turn is complementary to the entrance door with its horse–shoe arch below. The similarity with entrance composition of the cave temples at Nasik, Kondane or Ajanta, Maharashtra is obvious.

The horse–shoe arch supported on the double pilaster at each end, shows a scroll ending, which is the symbol of scripture as used in the Sanchi Stupa gate. The monogram of the Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission in a lattice work fills in the horse–shoe fittingly. Hindu religious symbols like elephants, lotuses and a Shivalinga sculptured by Sri Nandalal Bose completes the entrance gate composition.

The windows on either side of the entrance gate have suggestion of similar pattern in Moghul and Rajput palaces. The squarish projections at the extreme ends of facade topped by domes suggest of fortifications used in old Moghul Forts. Over all, the entrance facade gives an imposing effect made up in three tiers, springing of arch and pavilions.

The Interior

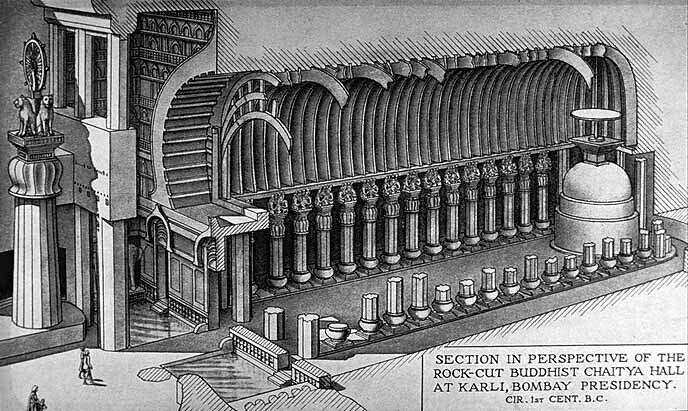

When one walks in and through the entrance, eyesight moves down the row of columns to the deity sitting at the end. The tall columns supporting vaulted roof remind one of the interior of the Buddhist Chaitya at Karle and the Kondane of Western Ghats, Maharashtra. However, the spacing of pillars and their design is far more pleasing unlike the sombre rows of rock–cut chaityas.

The wide nave, narrow aisles, windows alternating with niches and the Garbha Mandira attached to the Nat Mandira in a continuous space remind one of Christian churches especially in plan. However, the vaulted roof of the nave of congregational hall more aptly recalls to one’s mind the picturesque effect created in the Chaitya at Karle where rows of wooden arches raised from column capitals used to allow a play of light and shadow.

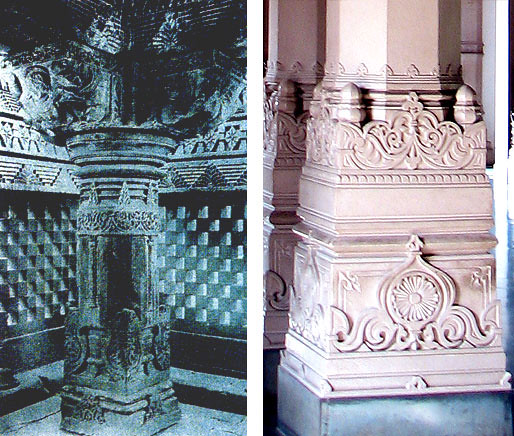

The Column

The long row of single pillars is interrupted by a set of double pillars on both sides of the side entrance, complementing the entrance. The pillars have a tall base, an octagonal shaft and richly ornamented capital. The capital reminds one of the Orissa style with foliage in a replica of decorative pot and bells hanging down the sides.

The beam above is supported by decorative brackets which remind one of the brackets in South Indian temples. The projected balcony supported from the beams by brackets with the pillars below are similar to those at palaces of Fatehpur Sikri.

The Garbha Mandira

The Garbhamandira or the main shrine itself, unlike those in Hindu temples which have little or no light, is very well lighted and ventilated. Hindu temples had to resort to closed shrines during Muslim invasions and, to create a feeling of humility as well as to provide protection, have a low entrance to it. But the vision of Swami Vivekananda of the all–embracing openness in the religion of Sri Ramakrishna foresaw the use of the shrine by millions without restriction. The walls of the shrine inside and outside towards the Natmandira (congregational hall) are pure white in contrast to the warm light buff colour of the hall. The arches and lattice work remind one of the Mughal Diwan-I-Khas at Agra.

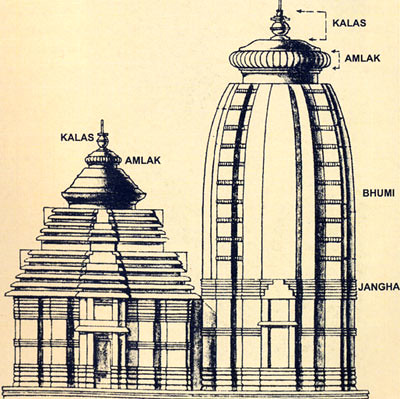

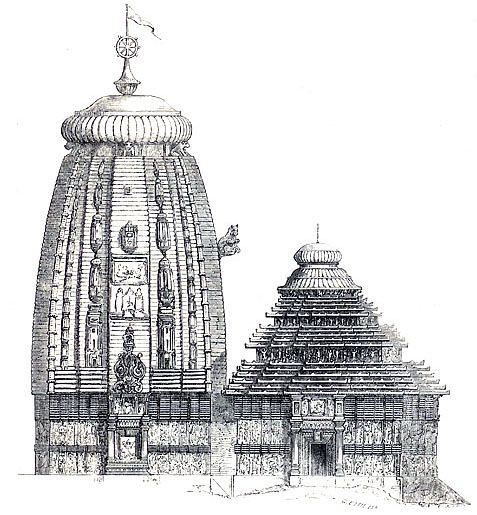

The Natmandira and the Garbhamandira is connected by a neck, a shortened form of Jagmohan of the Orissa temples with two side entrances and a space meant for the party singing devotional songs.

The white marble statue of Sri Ramakrishna sculptured by Sri Gopeswar Pal which has variety of moods as per play of light and shade is proportionate to the scale of the temple and is placed on a beautifully carved fully blossomed lotus set on a moderately decorated drum (damaru) shaped marble platform designed by Sri Nandalal Bose. The idea finds its echo in the statue of Buddha at Kanheri or that of Lakshmi at Ellora. The origin of Lotus Seat (Padmasana) of the deity is in yogic meditations.

The Circumambulatory Path

After having darshan of the deity, one passes through the side doors of this Jagmohan on a circumambulatory path (pradakshina vithi) around the Shrine which reminds one of that at St. Peter’s or Chaitya halls.

The pradakshina is highlighted by the lattice work statuettes of nine planets (Shani, Rahu, Ketu, etc.) carved by Sri Nandalal Bose and reminds one of such statuettes at the Hindu temples.

The Shrine Roof

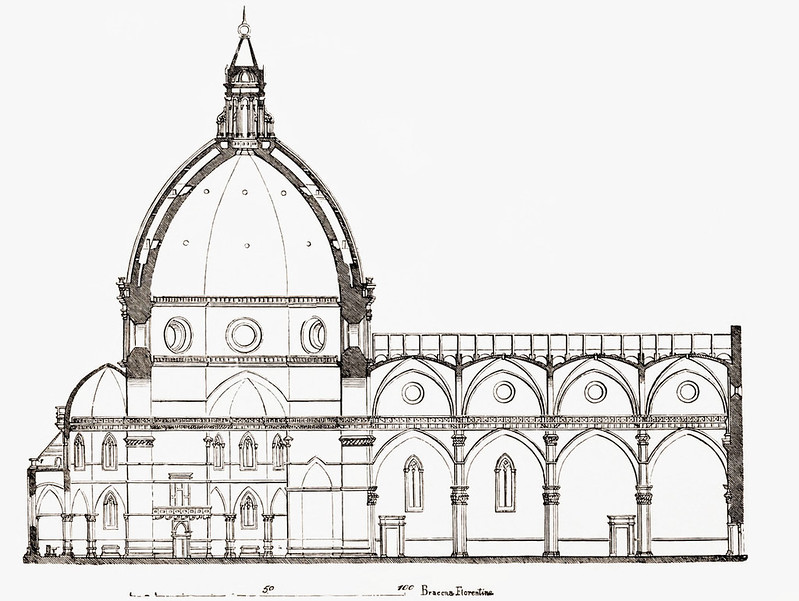

The circumambulatory path along with the shrine is surmounted by a beautiful pyramidal composition of domes and pavilions. The central dome on top of the main shrine is similar to the dome at Santa Maria Del Fiore, Florence. The smaller domes are proportionate replicas of the central dome, total twelve in number. Surrounded by curvilinear pavilions along with eight domes, the central dome above the shrine creates a similar effect, though more heightened than in the tomb at Alwar). The curves of pavilions are more in the line of the Bengal temple roofs.

The central dome with its imposing appearance, ribbed perimeter topped with inverted lotus below a ribbed round stone called Amalaka crowning the spire is similar to that found in temples of Bhubaneswar.

Side Entrance

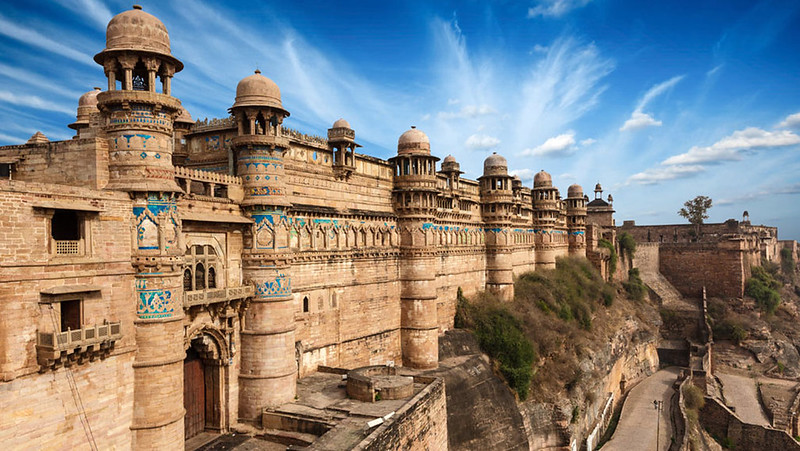

While going around the temple platform, one is attracted by the exterior of side entrances to the congregational hall. The entrance gate with two pilasters, pyramidal cantilever and two side columns resemble Elephant gateway of Maan Mandira at Gwalior Fort. The individual side column has similarity with the Victory Tower of Chittor, Rajasthan.

A statue of Sri Ganesha and Sri Mahavir Hanuman adorn the top of east and west gateways repectively as protector deities. The details of the parapet wall bear similarities with the city place of Chittor, Rajasthan.

The Temple Platform

Raising the temple on a 1.75 metre high platform (with a basement below) has enhanced its significance (God has to be reached with some effort) and its visibility to the individual visitor as in Khanderaya Mahadeo Temple of Khajuraho.

At the time of leaving the monument, one is impressed by the architectural variety of forms, styles, elements and details used in this temple harmoniously blended with each other and at the same time casting individual impact. The temple in totality seems to convey a feeling of entering a fort of divine assurance (palace of spirituality) delicately paying tribute to the genius of Sri Ramakrishna whose living presence is enhanced by the architectural motives associated with the culture developed around Bhagavan Buddha, Jesus Christ, Sri Vishnu and other great prophets and saints of the earth.